DIY NATION

The fast-growing world of China's hackerspace communities

“Shenzhen is the new Silicon Valley for hardware - there’s no supply chain like this anywhere else.”

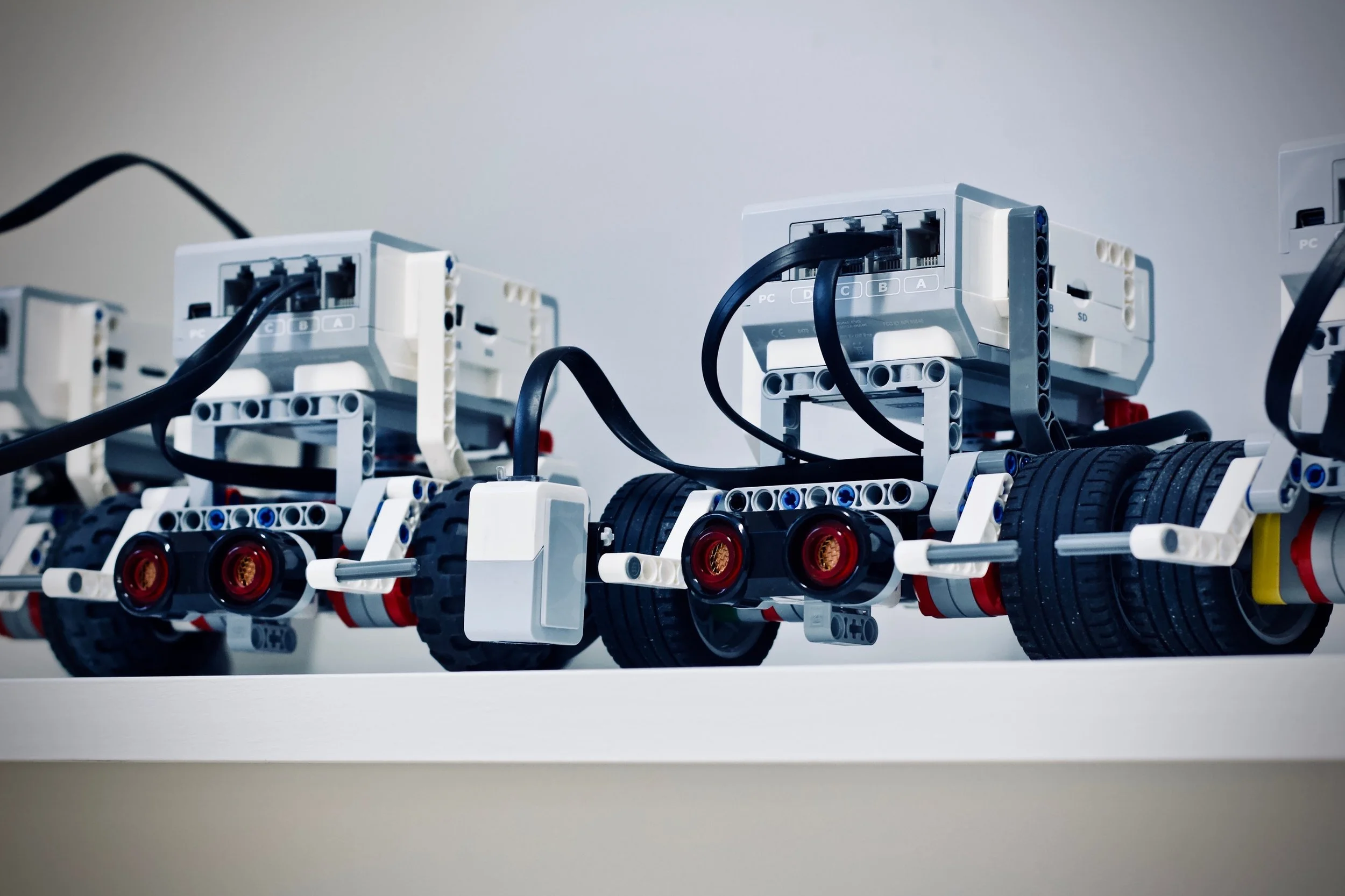

It is a chilly December afternoon in Shanghai’s Jing’an district and some 30 people are huddled together in a former office building, listening attentively to a presentation on how to build an Insect Bot – a small, spider-like robot, programmed to move across smooth surfaces when powered by a microcontroller.

The interactive workshop is hosted by XinCheJian, China’s first hackerspace (or makerspace as it’s also known, the two terms are used interchangeably), a community-run initiative where inventors, tech start-ups and ordinary people meet to experiment with everything from drones to 3D printing.

The converted office space is one of the few places where the phrase ‘mad scientist’s lab’ might be considered less a cliche, and more a factually accurate description. Inside there are laser cutters, metal shelves crammed with drill presses, soldering irons and miter saws, reams of wires, woodwork tools, circuit boards of varying sizes, a seemingly infinite number of screwdrivers, and, somewhat inexplicably, a battered leather armchair mounted atop a vintage motorbike.

The backdrop, while functional, is also something of a protective cocoon, a safe space for unabashed geekery. As the presentation draws to a close, those in attendance – mainly young, clean-cut men in their twenties and thirties – talk enthusiastically about the latest infrared sensors and rechargeable 3.7V LiPo batteries. A significant number of those gathered are bespectacled engineering or electronics students, here to put their learning into practice and showcase their skills. Others are mere hobbyists with a penchant for robotics or aspiring technology pros. One tall, scruffy guy who I strike up a conversation with turns out to be a former foreign trade analyst who quit his job to study computer programming.

The movement’s origins can be traced back to Berlin where, in 1995, a group of young programmers (hence the traditional use of the term ‘hacker’) pooled together and began sharing a workshop space. Defined by a highbrow, determinedly independent approach to technology, and a preoccupation with issues surrounding globalization, outsourcing and the growth of online communications, the Berlin-based community quickly grew (it currently boasts over 450 members), later spreading across Europe, with similar spaces developing in France, Italy and the UK.

By the early noughties, hackerspaces had made the leap to the US, where they lost much of their initial intellectualism, becoming more akin to a traditional home workshop – hence the term ‘makerspace’. Under this new guise, the community continued to develop, transforming slowly into an inclusive network for engineers and inventors to share ideas. Today, there are over 500 active self-proclaimed hackerspace hubs worldwide.

Over the last four years, the movement has gained ground in China too, helping to foster what former Wired editor Chris Anderson describes in his 2012 book Makers as the “third industrial revolution”: entrepreneurs, but also hobbyists, using open-source design, 3D printing and crowdfunding to independently manufacture products – often hybrids between art, technology and design.

It is a novel reality for China and one that moves to challenge assumptions about the country’s lack of domestic innovation, according to Silvia Lindtner, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan’s School of Information, who has been researching and studying Chinese maker culture.

“It’s no longer just about ‘Made in China’ in terms of manufacturing,” she says. “On the contrary, China is becoming an essential enabler in the global maker movement on an inventive level.”

Even the government is taking notice. On January 4, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang visited Shenzhen’s hackerspace, Chaihuo, where he stressed the “important role innovation plays in the development of the Chinese economy” and was named Chaihuo’s first new member for 2015. In November, Shenzhen Mayor Xu Qin released the ‘Shenzhen Declaration of Global Makers’ in a bid to express the city’s continued support for the community.

But Li and Xu may be, as makers are given to say, ‘behind the curve’. Officials have been supporting the growth of the movement as far back as 2011, when authorities in Shanghai announced a plan to launch 100 ‘innovation houses’ in the city, offering each up to RMB50,000 in funding. That same year, in the wake of China’s first Maker Carnival – an array of events centered around hackerspace culture – the Zhongguancun Municipal Government in Beijing announced plans to provide funding to further develop of the capital’s own hackerspace community. A year later, the Shanghai Maker Carnival drew sponsorship from the Communist Youth League.

The sudden influx of government funding mirrors the industrial development of Japan in the 1950s. Like China today, the economy of post-war Japan was built on manufacturing – with a focus on cheap, mass-produced goods. But by the late 50s, Japanese products, though more affordable than Western alternatives, were failing to keep pace in the international market. Aware of the apparent discrepancy, the government began to shift its attention toward product design. In order to compete globally, Japan would need to innovate, not imitate.

The result was the creation of a series of state-funded specialist design colleges – not dissimilar to today’s Chinese hackerspaces – where young people were able to share resources and trade ideas freely, a unique idea in the context of post-war Japan. The investment paid off and by the mid-60s, design had become a fundamental part of both the mass-production and mass-marketing of Japanese products overseas, with the country’s new ‘high technology’ aesthetic (perhaps best encapsulated by Sony’s early range of electronic goods) becoming a key driver in the country’s economic growth.

Whether China can repeat the success of its neighbor remains unclear, but the appeal – at least from a government perspective – is unmistakable. Innovation sells, nowhere more so than in the technology sector.

“It’s not just a bunch of geeks. Anyone creative can come and make cool stuff.”

Literally meaning ‘new workshop’, the Shanghai hacker space XinCheJian was established in 2010. What started as a handful of people in a one-room office, now counts among its members over 200 active makers working on a diverse range of projects, from a pocket-sized anti-theft device that sets off an alarm when detached from the item it guards, to a suspended hydroponic garden that uses artificial light and soilless cultures. A membership fee of RMB500 a month provides complete access to the workshop, as well as free entry to weekly hands-on seminars and occasional special guest lectures.

“Since we first launched, 30 independent hackerspaces have opened their doors across the country,” says David Li, the Taiwan-born programmer who co-founded XinCheJian. “DIY culture is being remade here. It has been a little slower than in other countries, but grassroots innovation is picking up fast – and in a unique way. We’re seeing a maker movement with Chinese characteristics.”

The characteristics Li is refers to are related, somewhat paradoxically, to the community’s close proximity to so-called shanzhai companies centered in Shenzhen, China’s high-tech hub. Although the word shanzhai is often used pejoratively to describe local copycat manufacturers making electronic devices based on shoddy knock-off brand names – think “Nakia” and “Anycall” – the specialist sector may be providing young Chinese makers with an edge over their international counterparts.

“Being so close to the supply chain allows anyone with a good idea to turn their prototypes into small-scale production runs,” says Li. “The Shanzhai economy is helping to redefine innovation in China. It’s an integral part of contemporary DIY culture, for both local and international hackers.”

This is the reason why engineer-turned-entrepreneur Pan Hao, who also goes by the English name Eric, chose Shenzhen to open Seeed Studios in 2008. Sitting at the intersection of industrial manufacture and hackerspace culture, Seeed helps makers source, design, produce and commercialize their ideas. Encourages people to propose and pitch projects on-site, the studio offers help making quick prototypes and manufacturing small orders.

“DIY culture is being remade in China.”

“Let’s say you are a maker with a limited budget to get your project into production,” says Pan. “Seeed gives you the tools – from open-source hardware like electronic components to crowdfunding services – to bring your concept to life. It’s a bottom-up approach to creativity. You no longer need to be an engineer to realize your invention and sell it on the market. We do that for you, right here in Shenzhen.”

With its abundance of cheap labor, suppliers and service providers, the sprawling southern metropolis has become the epicenter of the Chinese makers culture. “It’s the Hollywood of hardware,” says Pan.

If Shenzhen is Hollywood, then Seeed is its MGM studios. Started as a two-person company, the group (motto: ‘Innovate with China’) now counts a staff of over 100. Having worked for some 200 makers, it has become one of the world’s biggest providers and manufacturers of technology for small-scale innovators, with annual revenues exceeding USD10million.

In 2014 alone, the company brought almost 500 projects to market, from both domestic and international entrepreneurs-turned-inventors. They range from a WiFi and Bluetooth sensor in the shape of a chocolate bar to a low-cost 360-degree laser scanner with a six-meter distance detection range.

In the process, Pan has earned rock-star status among the global hacker community, making the cover of Forbes China in 2013 as one of the country’s 30 ‘Innovators Under 30’. He is also the founder of Chaihuo, the makers studio that recently welcomed Premier Li. “[The visit] marked the beginning of a crazy year for the maker movement. In a good way,” he explains. “We now have a newfound legitimacy we could only dream of before. It’s exciting.”

Since 2012, Pan has organized Shenzhen Maker Faire – a range of workshops, exhibitors and demonstrations under the general umbrella of DIY culture. The initiative welcomed an estimated 30,000 attendees last year, cementing Shenzhen’s position as a global capital for makers.

“The Faire is a showcase of invention, creativity and resourcefulness, and a celebration of the maker movement,” says Pan. “It attracts makers from all around the world – garage tinkerers, tech enthusiasts, programmers – but also families, students and big companies looking to tap into the vast resources of the Shenzhen ecosystem.”

Cyril Ebersweiler, a venture capitalist based in Shenzhen, has been regular at the Faire since its debut and shares Pan’s infectious confidence about the city’s development.

“In Shenzhen you can have a new connected device made in three days. In the States you would need weeks,” he says.

Founding of Haxl8r (pronounced “Hackcelerator”), a company similar to Seeed, in 2011, Ebersweiler offers mentorship-driven funding programs to foreign and Chinese start-ups. Companies entering HAXLR8R receive USD25,000 in funding and get access to professional mentors from the tech community, before being invited to Shenzhen to work on their products.

“This is the only place we could do this,” Ebersweiler argues. “Small companies here are willing to work with start-ups, and that opens a whole host of possibilities for ideas, concepts and manufacturing. Shenzhen is the new Silicon Valley for hardware – there’s no supply chain like this anywhere else.”

But there’s more to the Chinese maker movement than merely a drive to make commercial products for the global market. Places like XinCheJian or Chaihuo are becoming social and ideological forces, says the University of Michigan’s Silvia Lindtner.

“Makerspaces are redefining the way people think about work and engagement in China. They are hives of innovation; real-world communities where members can do what they love, take risks and play – not just remake technologies.”

“In Shenzhen you can have a new connected device made in three days. In the States you would need weeks.”

Make Plus, a Shanghai project launched in 2013 by a group of XinCheJian members, hosts collaborative events that blend art and technology for the local maker community. Hoping to develop a sense of maker culture, the group is made up 20 volunteers and its events attract anywhere from 20 to 100 attendees. Co-founder Sophia Lin calls it “more [of a] theoretical, artistically experimental approach to the maker movement.”

Also in Shanghai, MFK (Make for Kids) is a platform targeting a younger generation of future makers. Encouraging cross-disciplinary, peer-to-peer learning, and promoting cooperation through open source software and hardware, MFK offers courses in 3D printing, physical computing, sewing, robotics and electronics to children and teenagers aged 7-15.

In Beijing, Hackathons have become popular events among local makers and students. These 24- to 48-hour events see computer programmers, graphic designers, interface designers and project managers come together to collaborate on software and businesses spanning the useful to the weird.

Reflecting on the growth of the movement, founder of Beijing Makerspace Wang Shenglin (or Justin Wang), highlights the importance of community. “The main reason why I started Beijing Makerspace was to give people with a common interest a platform to experiment together and turn technology into something accessible to anyone. Like music.”

According to Wang, a former Renmin University finance graduate, as many as 60 percent of Beijing makerspace members primarily attend for fun. “They are IT engineers, programmers, designers, artists, students – even kids. They share ideas across mailing lists, collaborate on projects and attend tech and arts events. It’s not just a bunch of geeks. Anyone creative can come and make cool stuff. It’s a real community.”

Located in an open, industrial space in an unassuming office building in Zhongguancun, the capital’s electronics hub, Beijing Makerspace is similar to XinCheJian, if bigger in size. Centering on a sparse communal area, with a few scattered chairs and a foosball table (even hackers need some old-school distractions, says Wang), the space is alive with a variety of ongoing projects. On one side of the room, a quadcopter – a miniature helicopter-like drone used for aerial mapping – is preparing for takeoff while, in an adjacent room, a small robot scoots about on wheels.

Like its Shanghai’s counterpart, Wang’s lab also started as a tiny space – a 20sqm room – in 2011. It now covers 1,000sqm, boasting over 10,000 subscribers to its mailing list and collaborating with global companies including Sony and Samsung, who have granted Beijing makers access to their research labs.

“There’s a lot of educational and financial potential in what we’re doing,” says Wang, who has just returned from a meeting with Microsoft. “One of our makers might develop the next big thing in the tech field. Hence why the higher ranks – both the government and industry giants – are keen to get involved. They are curious.”

XinCheJian’s David Li is of the same opinion: “Maker culture is seen as a means to bring economic competitiveness forward. Everyone wants to have a piece of it.”

But might such top-down support – particularly from the government – clash with the grassroots essence of the maker movement? Both Wang and Li believe that, for now, this isn’t the case.

“You can’t have any movement of our size in China without government approval,” says Wang. “[Its] involvement allows us to pay rent, work on our own projects, host fairs and initiatives – all essential if we want to bring DIY culture forward.”

“The hardest aspect [of] makerspaces is financial sustainability,” adds Li. “And if institutions or bigger tech companies can help then I’m not opposed to it in principle. Hackerspaces give Chinese hackers a community – and we want to keep that going.”

Image: wiki.xinchejian

First appeared in That's Shanghai, That's Beijing and That's PRD magazines, February 2015.